- 15 January, 2025

Legal tech has been a notoriously unexciting category for VCs, but that’s shifted recently with a clear rising tide across the segment, driven by LLMs.

We’ve met dozens of companies finding commercial inflection points in the past 6 months, which is particularly exciting in a sea of LLM-powered applications where product-market fit has been tough (how many are you a weekly-active-user of?). This has led to a flurry of top tier deals in Europe and even some exits (e.g. Henchman by LexisNexis), which is always great to see.

Earlier this year, we decided to dig into this trend on a deeper level – and interestingly, it became immediately obvious that there was a distinct lack of consensus in this category, relative to other segments we’ve looked into. We spoke to many smart people (lawyers, operators, buyers and sellers of legal tech, investors and founders) and everyone was very split on many core questions, such as: Should you focus on in-house or legal-firms? Are off-the-shelf models sufficiently accurate? Is the market big enough for venture-scale outcomes?

So over the last few months, we’ve looked at the data and spoken to a broad network of founders, law firms and in-house counsel to draw some insights. This post acts as both a primer to the segment but also touches on some key findings for recent developments.

A quick intro to legal tech over the years

- Wave 1 (2000 – 2010): SaaS to catalyse a shift to electronic legal workflows, for example DocuSign and LegalZoom.

- Wave 2 (2010 – 2022): Advances in rules-based NLP, mostly around document management systems. Search was the path of least resistance for legal automation, for example Contract Lifecycle Management systems (CLMs)

- Wave 3 (Present): More complex workflows faced resistance and required “reasoning” – the ability to translate legal knowledge was highly complex and required lots of manual labelling, which didn’t scale

Historically, the necessary legal knowledge required for automation has been encapsulated in natural language, but now large language models are breaking these barriers down.

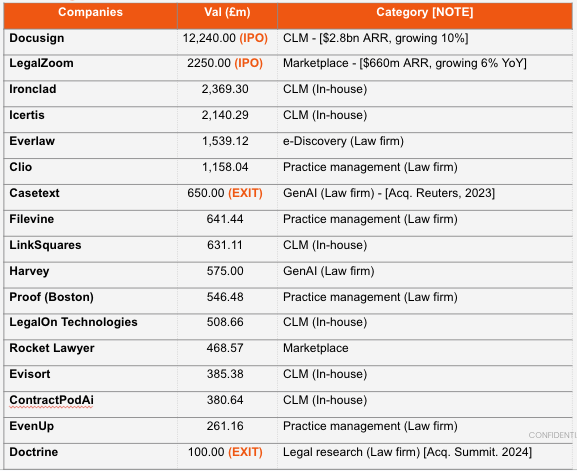

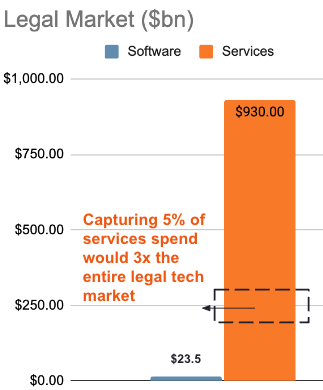

A quick (and non-exhaustive) Pitchbook scan reveals that there have only been a handful of sizeable venture-backed exits in legal tech, which is surprising given the magnitude of this market (~$1tn inc. services). The reality is, and as we explore in more detail in the next section, there are many structural hurdles to legal tech, not just technical ones.

The two largest IPOs are DocuSign and LegalZoom. These two companies catalysed a shift to electronic workflows, against the odds and a lot of resistance – indeed, for a period of time, both services were rejected by court. They overcame this resistance by building a strong network effect around their services, and we believe there will be startups which can do the same for AI-based workflows. There are some sizeable PE-backed players in e-Discovery such as Relativity, Epiq and DISCO worth noting. This is a highly interesting “services” category, which we explore further below.

We can see two established SaaS categories historically 1) CLMs (with IronClad and Icertis leading the way) and 2) Practice management tools (with Clio leading the way). It’s clear that GTM drove success in previous venture “winners” with very little product differentiation. Both Ironclad and Icertis saw success in an early GTM targeting big logos to drive a flywheel of trust in adopting these tools. Clio won with a high focus on customer success (e.g. Clio Academy), when executing their early SMB motion.

Top venture-backed legal tech companies. Note the concentration of CLMs and practice management solutions

Why now?

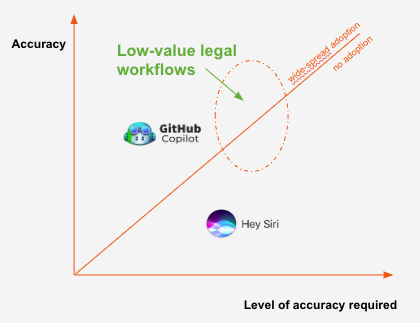

Despite the level of demand for genAI from enterprises there’s a clear lack of PMF at the application layer and most ARR is experimental. Legal tech is a rare hot spot of genAI PMF (or at least, model-market-fit) – in hindsight, this should be expected as there’s an ultra-high alignment in what LLMs are fundamentally trained to do and what legal work is.

Having spoken to many lawyers in many segments – there’s no denying that off-the-shelf models (especially post GPT-4) are able to accomplish low value legal workflows (e.g. drafting summary memos, NDA review, service agreement review) – resulting in a 10x efficiency gain in these workflows.

AI really seems to be the final straw that will break the camel’s back in a (mainly competition driven) shift away from billable hours, which has been one of the main hurdles to technology adoption in legal services. There’s an explicit disincentive to be more productive when charging by the hour but we’ve spoken to multiple SME firms who are being forced to shift their business model away from billable hours and towards value-based work, having adopted AI. Work which previously took a few hours can now be completed in 20 minutes.

There’s a massive appetite to adopt legal tech from larger house-hold name law firms but there’s no avoiding the fact that much of this is driven by herd mentality rather than actual value creation. There are power users at these firms demonstrating a positive direction but it’s still early and workflows are simple.

Much of this excitement was catalysed by the HarveyAI and A&O partnership last year, which opened the flood gates for other magic circle and US law firms to start adopting AI as clients start to demand it.

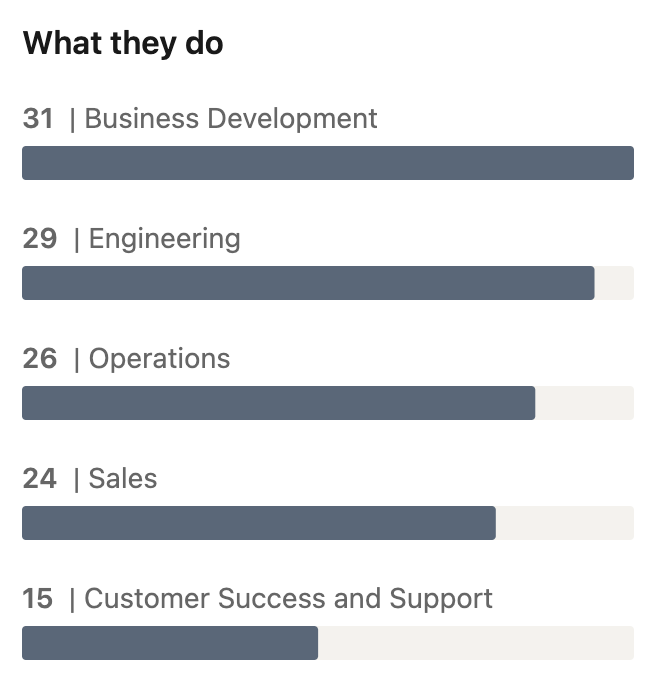

HarveyAI is now one of the fastest growing B2B SaaS companies ever having exploded to a $715m valuation just over a year after being founded. They are managing to break into the top 100 firms, where most of this market is concentrated, at a rate no company has done before. Our research suggests that, similar to other legal tech winners, this success is due to a strong sales and marketing engine rather than product / tech differentiation. This can be seen in the unusually large bizdev and sales division for a company of its age – they’re hiring many ex-lawyers who understand what it takes to break these firms. Harvey’s now shifting gears once again and is eyeing a $2bn valuation with hopes to acquire a legacy legal research company vLex in the process.

Breaking down the market

Mapping the legal tech sector can feel futile – there are many attempts at doing this but it often ends up being very convoluted. This is due to a lack of clarity on how emerging players weigh up against incumbents – as highlighted earlier, there are a lack of winners to create a skeleton. For completeness, I threw together my own convoluted map:

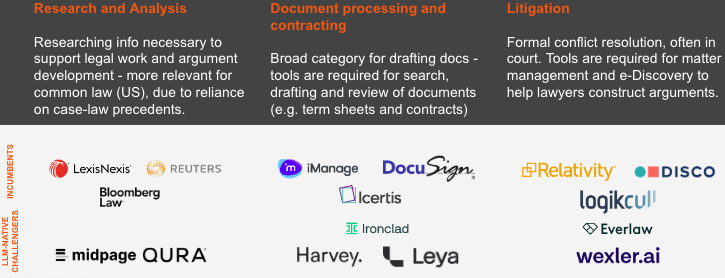

The best framework I’ve come across was from a recent report from Stanford where they map by client-facing verticals – this makes sense when we see LLMs taking on e2e legal work.

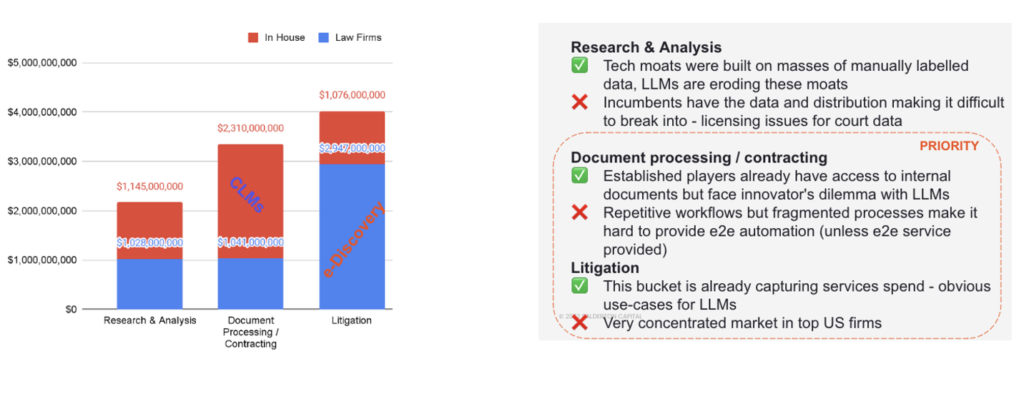

They’ve helpfully estimated some market sizes for these verticals as well – we can see in-house document processing (predominantly CLMs) and litigation tech for law firms (predominantly e-Discovery) are the more interesting segments. However, all of these individual numbers are smaller than the typical TAMs we’d normally get excited by in VC – we believe that venture-backed winners will offer full-suite products and should be able to sell to both in-house and law firms. However, each of these verticals could act as a great wedge and we discuss some pros / cons below.

Opportunities on the horizon

AI enabled law firms

As highlighted above, the legal tech market is promising holistically but small when you start to slice it. However, when you look at the legal services market, the numbers trump any SaaS TAMs. If startups companies can access this services spend whilst maintaining software-like margins, there’s a lot of reason to be excited. We’ve seen many examples of this:

It’s also worth highlighting Lawhive, which is a consumer law marketplace now building out verticalised AI features to perform the grunt work for onboarded freelance lawyers. The marketplace model allows them to easily capture services spend and also capture a huge amount of feedback data between consumers and lawyers. The business has similar characteristics to DocuSign and LegalZoom in catalysing a shift to AI-powered workflows with its network effect.

AI-native editors – Github Copilot for Law

Startups which can shift lawyers out of word and into cloud-based environments will be able to capture a treasure trove of data and RLHF loops, enabling genuine differentiation at the model layer (i.e. Github Copilot for Law). We’ve seen early signs of success in companies building AI-native editors with some lawyers spending many hours per day in these web-based applications (e.g. LegalFly, Juro and Genie) – a key factor to consider is enabling Word compatibility (i.e. smooth red-lining, import and export).

We’ve seen many companies find success as Word plugins by fitting into lawyers established workflows. Draftwise and Henchman are both plugins in the “clause bank” category, allowing lawyers to immediately surface clauses from precedent documents and broader knowledge bases. Law firms love this feature as it replicates for the painful workflow of internally asking “has anyone done this before?”.

However, there are many limitations:

- Limits product surface to sidebar, limits more complex workflows

- Limits ability to capture data on edits, limiting data flywheel

- Limits product velocity, plugins cause issues for security review

- Platform risk when building on Microsoft

- Difficult to capture network effects in sharing / collaboration

e-Discovery – A services market, ripe for disruption

e-Discovery is “a digital investigation focused on finding evidence in emails, business communications and other electronic data for use in litigation”. i.e. it’s the process of surfacing evidence for legal arguments – there’s no legal “reasoning” required, just pure fact finding. Due to the “low value” nature of this work, it’s often outsourced resulting in massive legacy [tech-enabled] services companies in this category such as Relativity and Epiq.

Everlaw is one cloud-native player worth highlighting but this is an obvious area for startups given the legacy nature of established players. Today there’s a lot of rules-based NLP to review documents today but there’s heavy human input involved – LLMs will transform how most of this work is done.

It’s worth noting that $billions of litigation revenue are dependent on these services so a rip and replace will be hard. Many firms are also able to pass on the cost to end-clients during litigation, resulting in a low incentive to shift away from these services.

However, this sits in the category of “crack the case” software so if a company can prove they’re better at finding facts and helping win cases then firms will pay huge sums for these services.

Sivesh Sukumar

Sivesh Sukumar