- 15 January, 2025

This is post five in a six-part series on mistakes European startups make in expanding to the US market. The previous post discussed hiring the wrong people. This post addresses another mistake, popular in particular with product-oriented founders, which is underestimating the importance of sales and marketing (S&M).Underestimating the importance of S&M takes one of several forms:

- Holding (and/or harboring) a belief that your product is the best in the market and it will win because of that alone.

- Underinvesting in S&M to fund R&D because you believe doing so will ensure you have the best product.

- Forgetting who gets to define “best.”

- Under-hiring S&M staff.

- Neglecting industry analysts.

The Best Product Doesn’t (Necessarily) Win

Everyone knows at an intellectual level the best product doesn’t win. Most founders know to repeat that like a mantra. Often, they’ll add the word “necessarily” to the statement: the best product doesn’t necessarily win. While correct, the addition sometimes includes a silent presumption that we, of course, have the best product — the first telltale that perhaps the founder doesn’t actually believe the statement.But sometimes, you genuinely, objectively have superior technology. It’s not a matter of fit or opinion. Surely, in those cases, the best product does win, right? Not so fast.My first job out of college was at a startup founded by four UC Berkeley professors that had simply stunning technology, but still lost in the market. Decades later one of our founders won a Turing Award, thanks to his technical brilliance. But our competitor’s founder ended up one of the richest people in the world, thanks to his superior S&M. Because of that experience, I don’t just know intellectually that the best product doesn’t always win, I know it viscerally – it’s tattooed to my brain.There’s even a third level of understanding: not just knowing it, not just believing it, but taking perverse pride in it. Think: “At BigCo, we won in the market without having the best product. As a sales leader, that was the pinnacle of my career.” We didn’t have the best product, I won anyway, and am proud of it. That’s who you want selling your product. Whether it’s the best or not.

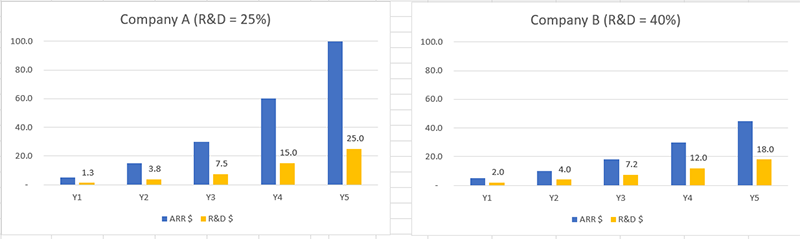

The Best Way to Invest in R&D is to Invest in S&M

It’s critical to be aware that “good product, bad S&M” launches a downward spiral. You lose share in the market, your revenue falls relative to your competition, and even if you make a relatively higher R&D investment, you will, over time, be unable to close the R&D budget gap. After the acquisition of the aforementioned company, the acquiring CEO tried to take perverse pride in our supposed lack of marketing prowess, literally saying at an all-hands meeting: “if you gave our marketing department sushi, they’d call it cold, dead fish.” Her intent was to use that as proof of product superiority. But that was nothing to be proud of. The combined company later went on to sell for a paltry 0.7x revenues. A destructive cycle, indeed.”Good S&M, bad product,” however, is self-correcting and launches a virtuous cycle. Every year you gain relative market share, spend a normal percentage of that on R&D, improve the product, and slowly and steadily close the product gap. In some situations, it takes a few years to catch up, in others, it might take a decade.What matters to the market is not state, but momentum. As long as you are perceived as leading in the market and gaining on product, customers will generally be happy to bet on the come that over time you will have the best product.This is why I often quip that the best way to invest in R&D is to invest in S&M.

The best way to invest in R&D is to invest in S&M

Forgetting Who Gets to Define “Best”

The other way to examine the “best product” question is to ask: who gets to define best? Sometimes founders can forget that the answer is, of course, the customer. And US and European customers may not define “best” in the same way.US customers tend to view technology purchases more holistically than Europeans. That is, they do not see themselves as performing some quasi-objective evaluation to establish who has the best technology in the market space. Instead, they view themselves as purchasing a solution to a problem and thus care about the quality of product, the fit with their needs, the quality of the vendor, and the ecosystem services and complementary tools. In the US, it’s not uncommon to hear quotes like this after winning a deal:

- “We didn’t think you had the best product, but you can do what we need, and we thought you were the vendor most committed to our success.”

- “We think startup X is clearly ahead of you in areas Y and Z, but we think you’ll catch up over time, and we like that you are established in the market and there’s strong availability of technical resources skilled in your solution.”

- “Your product is missing all kinds of features relative to the established vendors in the market, but we think you have a better platform, are moving quickly, and we like the direction you are headed.”

Hence the importance of S&M to position not only the product, but the company, its ecosystem, and its vision going forward. A myopic emphasis on the word “product” in “best product” can, particularly in the US, lead to disappointment when customers are shopping not just for a product, but for solutions to problems and a vendor with whom to partner.Note that companies pursuing product-led growth (PLG) strategies may have their own definition of “best product,” which is both customer- and onboarding-centric. In a PLG company, the definition of best may come from a cross-functional growth team consisting of sellers, marketers, product managers, and designers, all trying to optimize the product for onboarding and time-to-value. The best product, in a PLG context, is the one that I keep using, and keep using until I hit gates or paywalls that encourage me to upgrade to a paid or enterprise edition.

Who gets to define “best”? The answer is, of course, the customer.

Under-Hiring Sales and Marketing Staff

Companies who underestimate the importance of S&M tend to hire the wrong people to do it. Sometimes that’s because they’re being cheap. Think: if it’s not that important and not that hard, then, why hire expensive people to do it? For more on the dangers of day-old sushi, factory-second parachutes, and cheap people, please see the previous post in this series.Sometimes, under-hiring is due to not knowing what good looks like. If you grew up in startups working within engineering and product management, there’s a reasonable chance that you’ve not spent much time with world-class sales and marketing leaders. If that’s the case, there is an easy solution: go meet a bunch. Calibration, as peopleops types call it, here means setting up meetings with numerous, successful CROs, CMOs, sales managers, and sellers in order to develop your own sense for what they feel like.It’s like the old saying about trying to explain the difference between a Cessna and a 777 to someone who’s never seen an airplane. Or my real-life experience with dogs: all chocolate labs look the same until you own a chocolate lab. Experience teaches differentiation.This is a great use for your angels, advisors, and investors. Ask them for introductions to top people in sales and marketing. Then have coffee, lunch, or drinks with them. While this may eventually lead to some hiring downstream, it’s important that these conversations are purely networking and should be treated as such. Nobody wants to be invited to a calibration meeting only to feel like they’re being interviewed for a job, particularly when they’re not looking and took the meeting only as a favor.

Companies who underestimate the importance of sales and marketing tend to hire the wrong people to do it

Ignoring Industry Analysts

The last problem European startups face when it comes to underestimating the importance of S&M is ignoring industry analysts. For reasons that I don’t entirely understand, likely related to the history and evolution of the industry analyst business, European startups tend to consistently under-rate the importance of industry analysts. While I think this can cause some suffering in Europe, I think that suffering is more pronounced when expanding into the US.Industry analysts run the gamut from sole practitioners to public companies with hundreds of analysts. Just saying the word “analyst” usually conjures up one or more of the following:

- “They’re pay-to-play!” While a few at the low-end are more pay-to-play, the more legitimate and bigger firms tend to have a hard wall between sales and analysts, making them more pay-to-access. Anyone who’s ever tried to use money to move their Gartner dot will find themselves sorely disappointed.

- “They’re disagreeable!” Product managers (PMs) tend not to like analysts because they are often former PMs themselves and can ask hard questions in direct ways.

- “They’re only about vendors!” While some firms cater largely to vendors, the big ones cater more to Fortune 1000 companies. A typical analyst at a large firm might talk to dozens of customers per week – as well as a few vendors.

- “They’re just publishers!” True in a few cases, but most of them actively consult with customers to help them identify solutions, compare vendors, and establish evaluation short lists. Under the right circumstances, they can literally be a strong lead source.

The short answer is if you work with Fortune 1000 IT departments, you absolutely must work with industry analysts and if you sell pretty much anywhere else in B2B you probably should work with them as well. While an overview of analyst relations (AR) is beyond the scope of this post, European founders and executives should know three things:

- AR is a specialized job best handled by specialist consultants and firms (and not just handed to the PR firm)

- Founder/CEO participation in key briefings is important and a special advantage that startups have over larger companies (who typically delegate them to PM/PMMs)

- The best AR program is one that is focused on a small set of key analysts, focused on building relationships instead of transactions, and focused on the long term. You’ll know you did it right if ten years after the company is sold, you’re still having drinks with the analysts you used to work with every now and again.

In this post, we covered the five ways in which European startups can underestimate the importance of sales and marketing. In the final post in this series, we’ll discuss how European startups can hamper their US expansion efforts simply by looking and sounding, well, … too European.

European startups tend to consistently under-rate the importance of industry analysts

DAVE KELLOGG

DAVE KELLOGG