- 20 November, 2024

If you’re considering expanding your startup to new, international markets, you’ll need to juggle a lot of decisions, including timing, market choices, and budgeting. Here’s a look at some key mistakes you’ll want to avoid.

1. Going international too late

Going international too late is perhaps the most common mistake companies make. To be fair, it’s not always a mistake: Some companies never want to be international and prefer being a local success, even if that means lower long-term growth. For example, Dutch e-commerce business Coolblue generates over €1 billion ($1.14 billion) of revenues 20 years after launching and has never expanded further than Belgium.

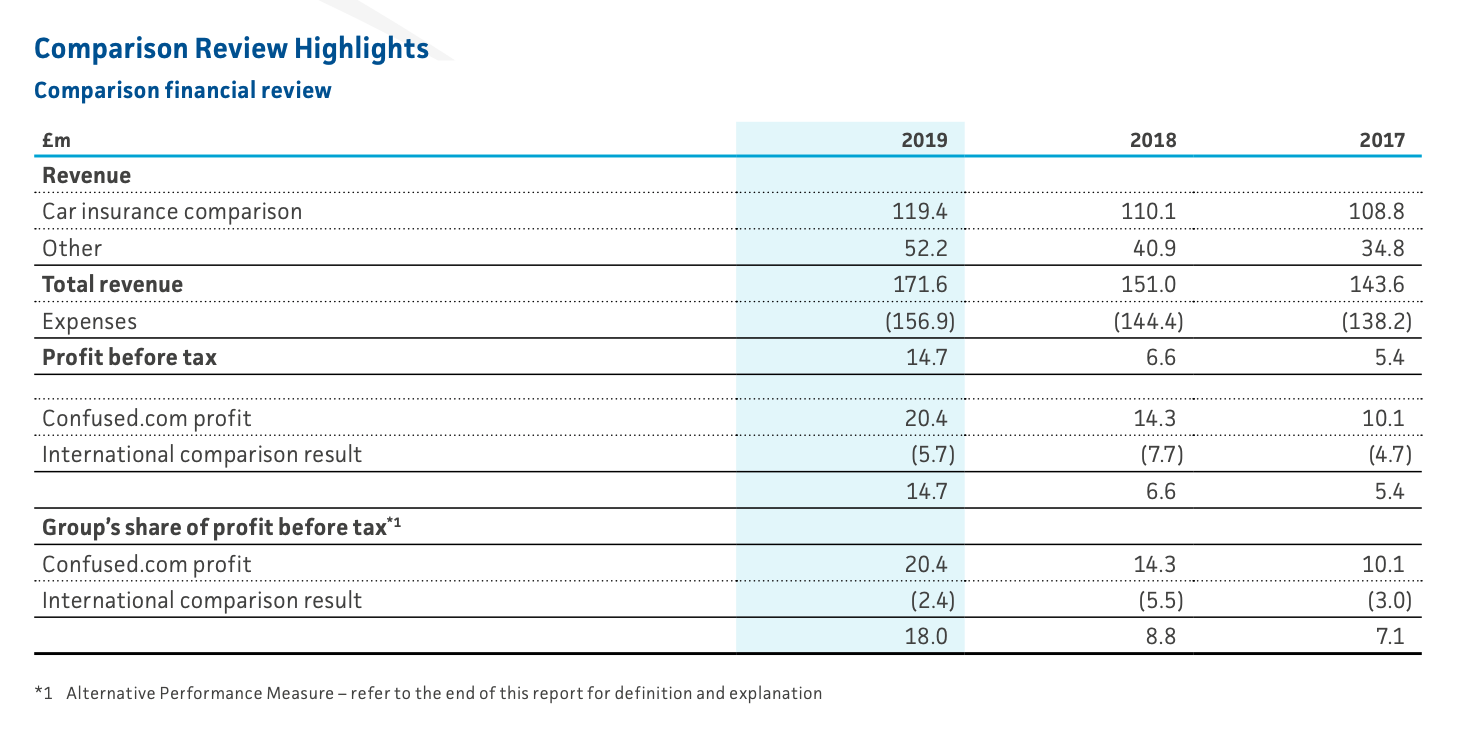

Examples of this problem are the British finance/insurance price comparison websites Confused and Moneysupermarket. These were pioneers in online insurance comparison and have reached $billion+ valuations in the UK, but they took many years to look internationally.

Moneysupermarket still has not managed to develop any significant international operations, and its share price has struggled as the UK market has become more mature.

Confused’s parent Admiral has belatedly invested in growth in the US, France, and Spain. It has faced some criticism for this, particularly its US operations, Compare.com, which were loss-making but seem to be making some headway:

Source: page 57 – Admiral Group plc · Annual Report and Accounts 2019

Traditionally, US tech companies were slow to come to Europe, leading to “copycats” popping up, often backed by Rocket Internet, which the US players would have to acquire (e.g. Groupon-Citydeal).

We see less of this these days, with Zalando, for example, far outperforming its inspiration, Zappos, and with US companies coming to Europe faster.

2. Going international too early

With venture funding more plentiful, we now see more of a challenge with companies trying to go international too early.

Often this is a company that is still refining its value proposition but has had some strong early growth in its home market. It decides to expand rapid internationally but then realizes there are issues in the core product. These are much harder to fix when the company is already spread across multiple countries.

One high profile example here is bike-sharing company Ofo, which expanded rapidly from China but more recently contracted international operations after facing strong competition and huge cash flow pressure at home. What really matters to Ofo and its competitors is being a winner in China, and this is far from done, requiring significant further investment — particularly with the rapid rise in escooters and ebikes. In this context, investing further in European growth does not make sense.

A homegrown example would be Housetrip, the vacation rental marketplace out of Europe. It grew very fast early on, backed by more than $50 million from Balderton, Index, and Accel. It is in a fairly international market of travellers and so grew rapidly across Europe and with US travellers. However, what really counted in the end was brand loyalty (repeats and word of mouth) in specific countries. When competition from Airbnb, Booking, and others pushed up the cost of performance marketing, Housetrip was left with the difficult choice of shrinking or growing uneconomically. A refocus just on the French and UK markets and a push to profitability led to an exit to Tripadvisor.

Rocket Internet has also had its share of challenges in copying US models that appeared to be working well, rolling out rapidly across countries, then realizing the proposition or economics have flaws. Its vacation rental play Wimdu shut down last year after a reported $90 million of funding.

Carpsring, a copy of Beepi, also shut down (although burnt far less money than Beepi did on its collapse).

3. Not budgeting enough to win internationally

Time for a Sun Tzu ‘Art of War’ quote:

If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles. If you know yourself but not the enemy, for every victory gained you will also suffer a defeat. If you know neither the enemy nor yourself, you will succumb in every battle.

Sun Tzu ‘Art of War’

The classic mistake here is expanding into a bigger market with a better-funded local player without a sustainable advantage over them.

A UK example is ride-hailing service Hailo. They were growing strongly in the UK and raised a total of $100 million to push from the UK into the US. While $100 million is a lot of money, it pales in comparison to the $1,500 million Uber had raised by a similar stage. Hailo didn’t know enough about its enemy’s ability to raise funds much faster and the sheer quantity of funds needed to build scale across the big US cities.

Arguably Hailo also didn’t know itself — its purported strength in working with regulated taxi drivers turned out to be a weakness.

For more reading see Fortune: Why a taxi app with $100 million in funding failed in the U.S.

What we see more often is companies raising Series A or Series B and setting aside $1-2 million to hire a US head and open a small US office to establish a toehold.

This very rarely leads to success. The company ends up split across multiple markets without making enough progress in any of them. Achieving success in the US requires significant sales and marketing investment, particularly when your competitors are well funded. Even with a regional US focus, your team is dragged across multiple cities and flights, and salespeople who interview extremely well can turn out to be mediocre. US prospects demand to see the founders, who may spend too much time traveling back and forth from Europe and are often jet-lagged.

Going early to the US can work. For example, my firm’s investments Aircall and Workable have made it work, but it requires real product USP, one or more of the founders to move there, a clear focus on the US market, and enough budget when compared to the competition.

4. ‘Proving’ international expansion in adjacent small markets

We often see German companies “proving internationalization” in Austria or Switzerland, or UK companies doing the same in Ireland.

Expansion to these adjacent small markets is usually easier, not requiring translation, product adaptation, a new office, or new logistics. However, because it is easier, you are not really proving your ability to grow in larger, more difficult countries. It still takes money, though, and is some distraction from your core market. It also delays when you can go to those bigger new markets. In most cases, it would be better to save that money to invest into success in a larger market or just show more growth at home.

For example, Hailo was a great success in Ireland, but that ultimately proved to be irrelevant. Starting international growth in small adjacent markets can also signal a lack of ambition to investors. There are always exceptions, but the reasons need to be clear.

5. Forgetting smaller markets

At a later stage in a company’s life, once they have been successful in major markets, good companies should also expand into smaller markets. These markets can often be the most profitable, and not adding them is leaving money on the table. Amazon, for example, has been slow to open retail in smaller European markets. They are still not active in Sweden and losing ground to the likes of Coolblue in the Netherlands.

Australia is another example of a market that was often neglected, leading to a range of ecommerce and online gaps and high margins for those who are active in the market.

6. Exclusive distribution partners

In an online world, relying on exclusive distribution agreements to expand to new markets is becoming rare, but it still pops up occasionally.

The temptation is realizing profits without requiring investment. The dangers are:

- Poor quality partner who doesn’t sell your product well (and/or goes bust)

- Your product message doesn’t translate well to the new market, but your partner can’t adapt the product

- Your product keeps changing, and your partner is always a year behind in how they think about it

- Your product is too small revenue-wise compared to the other products the partner sells and so their salespeople neglect it.

- Licensing your tech to other players in new markets shares similar risks. Partnerships can be great ways to accelerate, but for real international success you have to first show the ability to sell direct.

Ultimately, International growth is always hard, and no matter how well you prepare, it may not work out. All you can do is to try to avoid mistakes that have gone before.

ROB MOFFAT

ROB MOFFAT