- 09 April, 2025

Here’s a recent conversation I had with one of our founders:

Founder: “We are looking to bring on a Head of Talent to look after recruiting and the…HR stuff.”

Me: “I see. So a Head of People.”

Founder: “Well, no. People would report into Talent. Or should it be the other way around? I thought the People role is just HR. No?”

The conversation went on for another fifteen minutes. We discussed how the titles are defined differently in different hubs and who is responsible for what.

Why all this confusion?

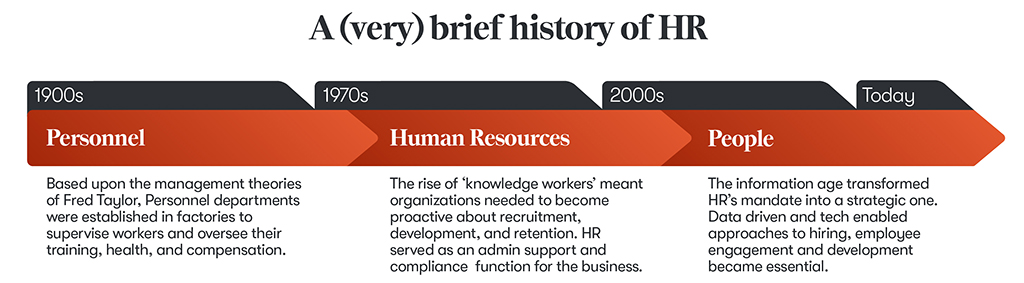

At the root of this is the fact that the tech community loves to hate HR, viewing it as a soulless, cumbersome function stuck in the past. Despite extensive efforts by respected academics like Dave Ulrich and practitioners such as Tom Haak, HR has not successfully moved past its legacy as a compliance and liability function.

In 2014, the New York Times reported that according to a Stanford study of dot-com boom startups, “tech entrepreneurs gave little thought to human resources. Nearly half of the companies left it up to employees to shape the culture and perform traditional human resource tasks.”

This perception still persists in tech circles despite notable achievements in HR in Silicon Valley. A well-known example is the 127-slide Netflix culture deck published in the late 1990s by then Chief Talent Officer, Patty McCord. It has been viewed millions of times and lauded by leaders such as Sheryl Sandberg as perhaps “the most important document ever to come out of the Valley”. McCord was in the role at Netflix for 14 years, working closely with founder Reed Hastings to build an exceptional team there.

The success of Netflix sparked a hot debate about the importance of culture in startups…

But it did little to elevate the HR function in the minds of tech leaders.

Another big moment for HR in tech companies came in 2006 when Google appointed Laszlo Bock as the SVP of People Ops. Here finally was a real chance for a paradigm shift.

Why?

Well, first, there was Bock himself, a Yale MBA grad, an ex-Mckinsey consultant who served as the VP of HR at GE prior to joining Google. Then there was the new name: ‘People Operations,’ or ‘POPS’ as it is known to Googlers. In his book Work Rules, Bock describes the rebranding as a way to gain credibility in the ‘engineering first’ environment of Google. Between his credentials, the new brand, and Google’s coffers, Bock was well equipped to give HR an extreme makeover.

Bock’s key strategy was to make People Operations at Google an omniscient, data-driven organization. This made a lot of sense. Empowered with data, the POPS team was more effective in convincing engineers to take action. Also, the timing was right. The Mid-2000s were a time when data analytics was on the rise in the Valley. In 2005, Tim O’Reilly published What is Web 2.0 in which he asserted that “data is the next Intel inside.” Business Intelligence tools like BusinessObjects and Tableau had become a must-have software, helping companies “unleash the power of their data”.

If Google wanted to set a new course for HR, there was no better way, or time, to do it than with data in the mid-2000s.

And so they did.

As Prasad Setty, who leads Google’s People Analytics department put it, they brought “the same level of rigor to people decisions that we do to engineering decisions. Our mission is to have all the people decisions informed by data.”But HR wasn’t only changing inside Google.

As this Linkedin video explains, the role of HR was evolving in response to market dynamics:

Where does this bring us in 2018?

Here we are. Over a decade later. And despite Google’s success and the rebranding of HR into the more holistic and strategic ‘People function,’ we still cannot say definitively that the battle is won. Not when People teams still struggle to not be seen as ‘HR’. Not when they do not have the same budget, influence, or perceived value as the technical and commercial teams in most startups. And definitely not until the People function can attract the same calibre of talent as other key functions.

These underlying problems cannot be solved with a simple rebrand. To cross the chasm, the first step is for founders and investors alike to acknowledge the vital importance of the People function. We need to be vocal about its impact on our companies (as Fred Wilson has done in this post and this one) so that we can inspire top talent to pursue a career in People. But none of this will work without proper investment of time and resources to build a robust People team that is empowered to do its job. At Balderton, we have been providing support to our founders on this for over seven years.

Defenders of the status quo will argue that early-stage companies do not have near the kinds of resources the giants have to invest in the people side of the business. This is true. But startups compete for the same talent with less cash and fewer perks to offer. So it is even more critical for them to get the People function right. They can win against the giants by putting people first.

Interested in learning more? Read our research on the people function here.